Market participants have grown increasingly frustrated at rising exchange-led data costs, as they struggle to keep up with a welter of new regulations on data usage.

Many believe that exchanges – which are amongst the biggest vendors of trading data – have been indulging in monopolistic practices, ramping up data fees as well as introducing complex and strict new data licensing measures.

With fee increases showing no sign of being curbed in the near future this is becoming a serious cause for concern for investors.

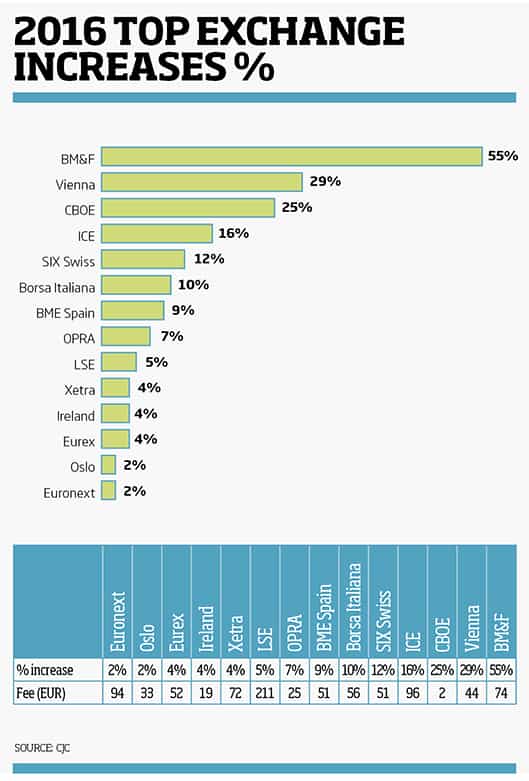

Data fees from exchanges have risen across the board over the past few years. Practically all the major European exchanges, including LSE, CBOE, NYSE Euronext and Eurex, have increased their overall data charges (see chart) from anywhere between 2% to 55% in 2016 alone.

Running concurrently with this, participants have seen exchanges introduce complicated new market agreements, breaking down data sets and charging separately for different types of data and incentivising end-users to trade by offering free data which is taken away quickly after. It is leading to a growing sense of discontent among buy-siders.

“If I am an asset manager with a trading desk in London and New York with five dealers on it – the one in New York will cost $16k for data while the one in Europe will cost $90k,” says Arjun Singh-Muchelle, senior adviser, capital markets at the Investment Association, the trade body for UK fund managers.

“The difference is enough to hire another dealer. We say there needs to be a competition review of data across Europe. There could potentially be an abuse of dominant market positions which could lead to monopolistic behaviour.”

Singh-Muchelle’s view is widely held. Mark Spanbroek, acting chairman of the FIA European Principal Traders Association (EPTA), an organisation representing Europe’s proprietary traders, explains: “Things need to be way more efficient and the pricing of market data needs to come way down. It is not a matter of time as we have waited long enough, and it is not going to happen unless someone drives this.”

Justifying costs

Buy-side firms are now more accountable to their investors as a result of the best execution requirements and are obliged to increase their sophistication in data capture and analysis.

“The evolving microstructure of most markets has become more fragmented with different venues, exchanges, dark pools, and so on,” says Michael Richter, director, Markit Trading Analytics.

“This creates a challenge for those looking to build accurate analytic benchmarks, for measuring best execution, and certainly is driving both the demand for data and the cost of acquisition.”

MiFID II has sought to step in, prompting a new level of data management and trade retention than seen before.

The regulation will force exchanges and other trading venues to price their data on a “reasonable commercial basis.” It also states that the price of market data should be based on the “cost of producing and disseminating it at a reasonable margin.”

Data charges will also have to be unbundled by disaggregating data by asset class, by country of issue, by the currency in which an instrument is traded, and according to whether data comes from scheduled daily auctions or from continuous trading.

Regulators now expect reporting mechanisms to provide investors with real-time information on market transactions across all execution venues, covering all asset classes. While the objective is to make trading more transparent for buy-siders the challenge to collect necessary data adds an exceptionally steep layer of complication.

However, market participants argue that the regulation over producing and pricing market data is too vague.

“We think that the regulation on market data has been watered down to such an extent that is has almost made them null and void,” says Singh-Muchelle.

He says that because the language used in the market data regulations is too vague, both regulators and market participants will not be able to judge what specifically a “reasonable margin is.

“The actual cost of the creation of that market data is not transparent. Without that information, how are we going to judge if it is a ‘reasonable margin’ or not?” he adds.

According to FIA EPTA’s Spanbroek, the regulation has not gone far enough to help curb rising data fees.

“MiFID II is not the solution to lowering costs. There is nothing directly in any of the delegated acts that will lower pricing, and I don’t see a role for clearing houses in pricing market data,” he says.

Market value

MiFID II states that the price of market data is determined by how market participants use the data. As a result, the regulation could give exchanges and data venues flexibility to price market data differently.

“Some may charge clients more than others, but I think they could do a much better job in building a pricing structure around this. For the prop shop community, they own this data pricing and a big part of the market data. So they are upset that this data is being sold, while also being charged by the exchange,” he explains.

In this sense, Singh-Muchelle argues that market participants are now beholden to the exchanges, as it actually encourages exchanges to discriminate how the data will be used and therefore increase prices for certain clients.

“The regulation states that market participants should have non-discriminatory access [to market data], but it then goes on to quantify for venues to discriminate how their clients use it,” Singh-Muchelle explains.

In addition, market participants are sceptical regarding the requirements for exchanges to unbundle pre-trade and post-trade data. In theory this should give customers more flexibility and choice, reducing their market data spends. However, the practice is likely to be very different, according to Singh-Muchelle.

“You can continue to bundle data from different asset classes,” he says. “If I’m an asset manager and want to buy exchange traded fund data I have to pay for all the equity data to get it.”

MiFID II also weakens competition between dark and light pools with more trading likely to be forced onto the latter. It is feared that this, again, will likely add to the power of major incumbent exchanges to further raise data fees.

Jerry Avenell, co-head of sales, Bats Europe, believes the larger exchanges have been responsible for forcing much of the unjustified price hikes in recent times.

“Incumbent national exchanges have continued to increase already-high fees, and over-complicate their market data agreements – normally against a backdrop of falling domestic market share,” says Avenell.

“In effect, this means customers have been paying more for less. Our competitors have upped fees despite a plateau in market share. It’s worth noting that the majority of incumbent exchanges have seen market share erode in core indices. The LSE, for example, only trades around 40% of the continuous market in FTSE 100 stocks each day.”

For example, with the anticipated merger of the LSEG and Deutsche Boerse, it will effectively create a monopoly over the production of market data.

Furthermore the $5.2 billion acquisition of Interactive Data by IntercontinentalExchange (ICE) catapulted the exchange to one of the three biggest data vendors in the world, alongside Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg.

Breaking in

As a result, new vendors will find it incredibly difficult to break into the space even in a post-MiFID II world.

“We definitely need competition, but for newcomers it is incredibly difficult because in order to start providing data you have to connect to the existing platforms first,” argues Spanbroek.

Market participants have increased demands for a competition review into the monopolistic hold incumbent national stock exchanges have over market data.

In the meantime, one solution is for the industry is to agree on the introduction of consolidated tape, a provision that is not mandated for all asset classes in the regulation, as a means to provide a consolidated view of trade transparency

“Chopping up the data and segmenting pricing is ultimately up to the market to decide. But even if you sign up to Bloomberg or Thomson Reuters you pay for your own pricing. So we have had conversations within our own community about providing consolidated tape with the pricing we have,” Spanbroek adds.

Mark Hemsley, chief executive officer of Bats Europe, does not have high expectations that there will be a shift to a consolidated tape model as a result of the regulation.

He says: “The biggest problem that prevents there being a consolidated tape is being able to get the data at a reasonable price. If you were to buy different components of the data, the problem is that the incumbent exchange can still hike up their data charges.

“So the consolidated tape price has got to be at least the aggregate of those three market data charges, and I don’t think people will be willing to buy the consolidated tape product without a discount. If the input costs are too high then no one will want to buy it.”

Hemsley says he has very low expectations that the provisions in MiFID II will lead to a consolidated tape in the near-term.

He adds: “I think there will have to be a regulatory mandate for that to happen.”

With MiFID II looming on the horizon the prospect of more data burdens is very real for the buy-side. The storm over data fees threatens to crack the market. It remains to be seen how the exchanges will address this.